As evangelists charged with planting a church, our mission and agenda

by definition include a significant amount of interaction with unbelievers in secular society. The question quickly arises, however – is the church simply to be about its own welfare? Or do we also bear some responsibility to engage in social action? To what extent is the body of Christ called to be involved in social, political, and moral issues?

A rapid survey of the biblical and historical records yields mixed results. Certainly we are called to love our neighbor (Luke 10:27-37), to seek justice and mercy (Mt 23:23), to visit orphans and widows in their distress (James 1:27). The early church took such charges seriously – they were known for their sacrificial care of poor and prisoners, both believers and unbelievers alike. Such examples rightly put many of our modern, consumer-driven evangelical churches to shame.

At the same time, many have argued that Scripture is surprisingly silent in key areas like politics, women's rights, and slavery – Paul preached submission and service, rather than revolution (Eph 5:22-6:8; Rom 13:1); we are told to pray for our leaders, that we may live a peaceful, quiet life (1 Tim 2:2). This hardly seems to fit with the vision cast by liberation theologians and social activists.

The tension is not easily resolved – we simply cannot point to a single verse or convenient proof text that clearly defines the church's role in society. To find an answer, we need to look more deeply at the warp and woof of the Scripture. We need a biblical view of destiny and redemption. And here, the Old Testament prophets prove particularly helpful.

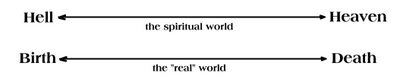

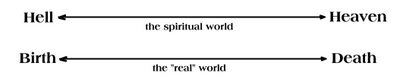

Modern evangelicals have often seen a sharp distinction between “spiritual life” and “the real world.” If we were to illustrate such a worldview, it might look something like this:

Many American Christians see the world of “spiritual things” as existing on something of a parallel plane to the here and now of daily living. Redemption is viewed primarily in terms of our personal destinies; the overarching concern of Scripture is seen to be equally individualized – people who are spiritually lost (usually defined as “not believing in Jesus”) somehow need to get themselves found (usually by believing the right things about Jesus, and living according to a certain moral code), thus ensuring an eternal future in heaven rather than hell.

In a perspective like this, the work of salvation is basically an intellectual commitment to “having Jesus as my personal Lord and Savior,” but my “real life” often continues mostly unchanged, and my “new life” doesn't really start until I “die and go to heaven.” The work of the church, then, is primarily focused on getting individuals to affirm the right facts about Jesus, that they might live happily ever after in the sweet bye-and-bye. There is very little real intersection between the two planes of existence.

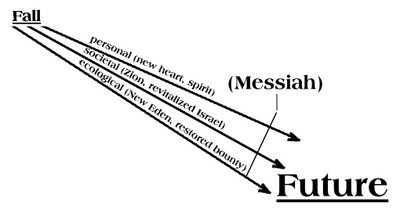

The Old Testament witness, on the other hand, paints a markedly different picture of future glory. As Donald Gowan points out in

Eschatology in the Old Testament, a prophetic view of the revitalized future is much more earthy, organic, and comprehensive – it envisions real life restored in the here and now, on earth (in the Promised Land, of course), rather than somewhere in the distant future. We might illustrate the prophetic vision like this:

Seen through the lens of the Old Testament prophets, “salvation” is not seen as some individual, personalized escape from this physical worldly existence to some future, other-worldly, streets-of-gold-with-harps-and-angels, spiritualized reality. No! Salvation is nothing less than a restoration of what was lost in Israel's fall.

Gowan unpacks this prophetic vision of restoration in three main categories. First, the prophets do in fact envision a

personal renewal. They promise that the Israelites will receive a new heart, one of flesh not stone (Ezek 11:19); it will be circumcised and holy (Deut 30:6), filled with the very Spirit of God himself (cf. Is 44:3) so they can serve God as he deserves and requires (cf. Deut 6). Second, the prophets also envision a

societal renewal. They look for the gathering of Israel from the nations to which she had been scattered, her renewal as a nation, her elevation to a position of national prominence, with Zion (Jerusalem) as the city of God, and a new and glorious temple set high on his holy hill (cf. Is 2:2+, Ezek 40+). Third, the prophets also envision

ecological renewal as the curses upon the land are reversed, in a virtual return to Eden as the land once more flows with milk and honey, and the river of life itself flows from the temple mount (Ezek 47).

The point here is simply this: the prophets offer us a much more comprehensive view of salvation, extending to all facets of life, rooted in the “real world.” In this view, the messiah represents the anointed one of God who will lead Israel into this new era of prosperity and blessedness.

This restoration vision becomes immensely practical when we see the connection between Christ and Messiah, between the New Testament church and Old Testament Israel, Zion (cf. Heb 12:22, 1 Pe 2:6, Gal 6:16). The redemption wrought by Christ is not merely internal, personal, spiritual (although it certainly

is that) – it reaches much further.

In fulfilling all the promises of God (2 Cor 1:20), Christ's redemptive work must carry implications for all three aspects. The promised renewal of society (nation) and ecology (land) are not merely future, nor are they figurative. The church needs to be salt and light in a fallen world, living redemptively and working for its transformation, seeking to illustrate the “already” of heavenly reality in the “not yet” of our present world. This is how the gospel will go forward. And this implies that the church's work in the world is more than mere proclamation – as Harvey Conn says, we evangelize most effectively when we minister both in word

and deed. The church has a responsibility to seek justice, to work for the social renewal, and we are given great liberty in terms of how we go about that task. At its best, the church should make a difference in culture and society.

Having said all this, we now need to make a vitally important clarification, one which redemptively minded Christians often overlook. Many who embrace this broader view of redemption (personal, societal, ecological) fail to consider for the surprising

way that Christ fulfills the promises of old. Restoration glory only comes through weakness, suffering, and humiliation – the Messiah comes dressed in the garb of a humble servant, rather than robed in the glory of a triumphant king. That reality represents a surprising twist on the old covenant story, one which actually affects the character of the fulfillment.

In the New Testament, suffering and humiliation is a key feature of Christ's calling – this is how he is perfected, how he gains his glory. While we get glimpses of it in the Old Testament (cf. Ps 22, Is 53), this feature is not fleshed out fully until Christ himself summarizes his ministry:

“Was it not necessary that the Christ should suffer these things and enter into his glory?” And beginning with Moses and all the Prophets, he interpreted in all the Scriptures the things concerning himself. - Lk 24:26,27.

Christ comes as the long awaited, glorious Messiah, and yet his glory does not come until his exultation, after his suffering.

As with the Messiah, so too the people who are formed in his image. We are saved through faith, yet we are not immediately translated to a state of glory. Instead, we too are called to a ministry that is characterized by weakness, foolishness, and suffering (cf. 1 Cor 1:18-25, 2 Cor 4:7-18, Phil 1:29). Our sanctification is progressive. We experience the fulfillment of the promises, but with a surprising already-not-yet texture to them. In personal redemption, I really do have a new heart that is changing me now. But I will not receive the fullness of that new heart, in all its overplussed glory, until Christ returns.

The promises are indeed

really fulfilled. But they are not yet

fully fulfilled. The heavenly reality of ultimate redemption is breaking into the here and now – the now-redeemed me is actually a the pointer to the then-to-be-redeemed me which is yet to come. So Christ, in fulfilling the promises of old, actually alters the trajectory of those promises, and fulfills them not in a single moment, but over the course of our lives, finding its full expression only at our glorification. If this is how Christ fulfills the promise of personal redemption, may we not also expect a similar fulfillment in the societal and land dimensions as well?

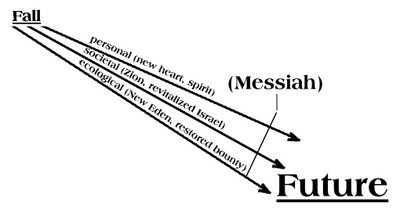

Once again, a diagram may help illustrate:

What we see here is the image of Christ as cornerstone (1 Pe 2:6-8). Not only is he the foundation of redemption, but he actually changes the trajectories of redemption as well – he “turns the corner” if you will, fulfilling the promises in a surprising manner. He creates a new people, a new temple, a new kingdom. None of these are altogether

different trajectories – there is a definite continuity with the old – but neither are they merely the

same trajectories. There is a reason why we speak of Christ's work as a “new covenant.”

Not only does Christ alter the trajectory of God's redemptive promises – as the cornerstone, he also acts like a prism which splits each line of redemptive activity and refracts them, giving them the already-not-yet character which we have described above for our personal salvation.

As with personal, so too the societal and ecological. Each line of promise experiences the same already-not-yet character of fulfillment: humiliation now, glory later.

This has deep implications for the way in which we engage in redemptive activity within cultural. Too many times, Christians recognize that Christ's redemptive work is broader than just personal salvation. This is good. Nevertheless, when it comes to societal and ecological redemption, we often look for a fulfillment that runs on the same rails as the old trajectory – through Christ (as exemplar, inspiration), yet with only a physical manifestation; there is real no heavenly dimension at all. We fail to appreciate how Christ has fundamentally changed the old trajectories. This is dangerous – it can lead to triumphalism at best, and a pure social gospel at worst.

To state the matter plainly, too often we look for social justice, or environmental renewal, or the revitalization of our cities purely in physical, earthly terms; we seek an earthly glory now, rather than the pattern of humiliation now, glory later. This makes it very easy for something like liberation theology to define its goals simply in terms of tangible, economic, “real-world” change. Such change is important. But at the end of the day when all these goals are realized, all you have done is create the very middle class which you started out critiquing. Redemption runs much deeper than simply transforming the working poor into the working middle class.

The same holds true for cities and ecology. We must never forget that Christ has

already restored the land, he

has created a new Zion. He has created the Kingdom of God, he has founded the one true church. These are spiritual realities, which can only be apprehended by faith. And so we as a church called to engage in real social action in the here and now, yet always pointing those we engage upward and onward to the deeper, truer, heavenly realities. The physical realities must never be seen as ends in themselves. The place where such expression happens most fully is the church (Eph 2:19-21) – this is where the work of Christ finds its climax; it is only natural that this is the place where his redemption accomplished should find its fullest expression.

In sum, then, the church has both responsibility and liberty to engage in social action. Our redemptive work in the secular sphere, however, must always be seen as secondary and derivative, and it must constantly point unbelievers back to the more ultimate realities of Christ's redemptive work in the church.