The Church and Social Action

As evangelists charged with planting a church, our mission and agenda by definition include a significant amount of interaction with unbelievers in secular society. The question quickly arises, however – is the church simply to be about its own welfare? Or do we also bear some responsibility to engage in social action? To what extent is the body of Christ called to be involved in social, political, and moral issues?

A rapid survey of the biblical and historical records yields mixed results. Certainly we are called to love our neighbor (Luke 10:27-37), to seek justice and mercy (Mt 23:23), to visit orphans and widows in their distress (James 1:27). The early church took such charges seriously – they were known for their sacrificial care of poor and prisoners, both believers and unbelievers alike. Such examples rightly put many of our modern, consumer-driven evangelical churches to shame.

At the same time, many have argued that Scripture is surprisingly silent in key areas like politics, women's rights, and slavery – Paul preached submission and service, rather than revolution (Eph 5:22-6:8; Rom 13:1); we are told to pray for our leaders, that we may live a peaceful, quiet life (1 Tim 2:2). This hardly seems to fit with the vision cast by liberation theologians and social activists.

The tension is not easily resolved – we simply cannot point to a single verse or convenient proof text that clearly defines the church's role in society. To find an answer, we need to look more deeply at the warp and woof of the Scripture. We need a biblical view of destiny and redemption. And here, the Old Testament prophets prove particularly helpful.

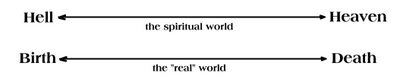

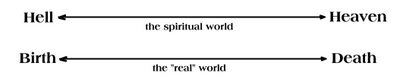

Modern evangelicals have often seen a sharp distinction between “spiritual life” and “the real world.” If we were to illustrate such a worldview, it might look something like this:

Many American Christians see the world of “spiritual things” as existing on something of a parallel plane to the here and now of daily living. Redemption is viewed primarily in terms of our personal destinies; the overarching concern of Scripture is seen to be equally individualized – people who are spiritually lost (usually defined as “not believing in Jesus”) somehow need to get themselves found (usually by believing the right things about Jesus, and living according to a certain moral code), thus ensuring an eternal future in heaven rather than hell.

Many American Christians see the world of “spiritual things” as existing on something of a parallel plane to the here and now of daily living. Redemption is viewed primarily in terms of our personal destinies; the overarching concern of Scripture is seen to be equally individualized – people who are spiritually lost (usually defined as “not believing in Jesus”) somehow need to get themselves found (usually by believing the right things about Jesus, and living according to a certain moral code), thus ensuring an eternal future in heaven rather than hell.

In a perspective like this, the work of salvation is basically an intellectual commitment to “having Jesus as my personal Lord and Savior,” but my “real life” often continues mostly unchanged, and my “new life” doesn't really start until I “die and go to heaven.” The work of the church, then, is primarily focused on getting individuals to affirm the right facts about Jesus, that they might live happily ever after in the sweet bye-and-bye. There is very little real intersection between the two planes of existence.

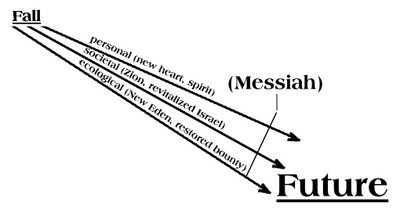

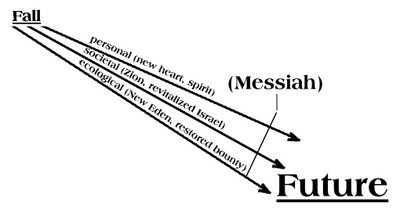

The Old Testament witness, on the other hand, paints a markedly different picture of future glory. As Donald Gowan points out in Eschatology in the Old Testament, a prophetic view of the revitalized future is much more earthy, organic, and comprehensive – it envisions real life restored in the here and now, on earth (in the Promised Land, of course), rather than somewhere in the distant future. We might illustrate the prophetic vision like this:

Seen through the lens of the Old Testament prophets, “salvation” is not seen as some individual, personalized escape from this physical worldly existence to some future, other-worldly, streets-of-gold-with-harps-and-angels, spiritualized reality. No! Salvation is nothing less than a restoration of what was lost in Israel's fall.

Seen through the lens of the Old Testament prophets, “salvation” is not seen as some individual, personalized escape from this physical worldly existence to some future, other-worldly, streets-of-gold-with-harps-and-angels, spiritualized reality. No! Salvation is nothing less than a restoration of what was lost in Israel's fall.

Gowan unpacks this prophetic vision of restoration in three main categories. First, the prophets do in fact envision a personal renewal. They promise that the Israelites will receive a new heart, one of flesh not stone (Ezek 11:19); it will be circumcised and holy (Deut 30:6), filled with the very Spirit of God himself (cf. Is 44:3) so they can serve God as he deserves and requires (cf. Deut 6). Second, the prophets also envision a societal renewal. They look for the gathering of Israel from the nations to which she had been scattered, her renewal as a nation, her elevation to a position of national prominence, with Zion (Jerusalem) as the city of God, and a new and glorious temple set high on his holy hill (cf. Is 2:2+, Ezek 40+). Third, the prophets also envision ecological renewal as the curses upon the land are reversed, in a virtual return to Eden as the land once more flows with milk and honey, and the river of life itself flows from the temple mount (Ezek 47).

The point here is simply this: the prophets offer us a much more comprehensive view of salvation, extending to all facets of life, rooted in the “real world.” In this view, the messiah represents the anointed one of God who will lead Israel into this new era of prosperity and blessedness.

This restoration vision becomes immensely practical when we see the connection between Christ and Messiah, between the New Testament church and Old Testament Israel, Zion (cf. Heb 12:22, 1 Pe 2:6, Gal 6:16). The redemption wrought by Christ is not merely internal, personal, spiritual (although it certainly is that) – it reaches much further.

In fulfilling all the promises of God (2 Cor 1:20), Christ's redemptive work must carry implications for all three aspects. The promised renewal of society (nation) and ecology (land) are not merely future, nor are they figurative. The church needs to be salt and light in a fallen world, living redemptively and working for its transformation, seeking to illustrate the “already” of heavenly reality in the “not yet” of our present world. This is how the gospel will go forward. And this implies that the church's work in the world is more than mere proclamation – as Harvey Conn says, we evangelize most effectively when we minister both in word and deed. The church has a responsibility to seek justice, to work for the social renewal, and we are given great liberty in terms of how we go about that task. At its best, the church should make a difference in culture and society.

Having said all this, we now need to make a vitally important clarification, one which redemptively minded Christians often overlook. Many who embrace this broader view of redemption (personal, societal, ecological) fail to consider for the surprising way that Christ fulfills the promises of old. Restoration glory only comes through weakness, suffering, and humiliation – the Messiah comes dressed in the garb of a humble servant, rather than robed in the glory of a triumphant king. That reality represents a surprising twist on the old covenant story, one which actually affects the character of the fulfillment.

In the New Testament, suffering and humiliation is a key feature of Christ's calling – this is how he is perfected, how he gains his glory. While we get glimpses of it in the Old Testament (cf. Ps 22, Is 53), this feature is not fleshed out fully until Christ himself summarizes his ministry:

As with the Messiah, so too the people who are formed in his image. We are saved through faith, yet we are not immediately translated to a state of glory. Instead, we too are called to a ministry that is characterized by weakness, foolishness, and suffering (cf. 1 Cor 1:18-25, 2 Cor 4:7-18, Phil 1:29). Our sanctification is progressive. We experience the fulfillment of the promises, but with a surprising already-not-yet texture to them. In personal redemption, I really do have a new heart that is changing me now. But I will not receive the fullness of that new heart, in all its overplussed glory, until Christ returns.

The promises are indeed really fulfilled. But they are not yet fully fulfilled. The heavenly reality of ultimate redemption is breaking into the here and now – the now-redeemed me is actually a the pointer to the then-to-be-redeemed me which is yet to come. So Christ, in fulfilling the promises of old, actually alters the trajectory of those promises, and fulfills them not in a single moment, but over the course of our lives, finding its full expression only at our glorification. If this is how Christ fulfills the promise of personal redemption, may we not also expect a similar fulfillment in the societal and land dimensions as well?

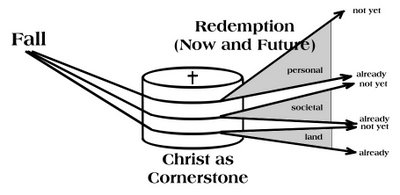

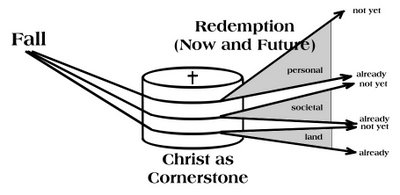

Once again, a diagram may help illustrate:

What we see here is the image of Christ as cornerstone (1 Pe 2:6-8). Not only is he the foundation of redemption, but he actually changes the trajectories of redemption as well – he “turns the corner” if you will, fulfilling the promises in a surprising manner. He creates a new people, a new temple, a new kingdom. None of these are altogether different trajectories – there is a definite continuity with the old – but neither are they merely the same trajectories. There is a reason why we speak of Christ's work as a “new covenant.”

What we see here is the image of Christ as cornerstone (1 Pe 2:6-8). Not only is he the foundation of redemption, but he actually changes the trajectories of redemption as well – he “turns the corner” if you will, fulfilling the promises in a surprising manner. He creates a new people, a new temple, a new kingdom. None of these are altogether different trajectories – there is a definite continuity with the old – but neither are they merely the same trajectories. There is a reason why we speak of Christ's work as a “new covenant.”

Not only does Christ alter the trajectory of God's redemptive promises – as the cornerstone, he also acts like a prism which splits each line of redemptive activity and refracts them, giving them the already-not-yet character which we have described above for our personal salvation. As with personal, so too the societal and ecological. Each line of promise experiences the same already-not-yet character of fulfillment: humiliation now, glory later.

This has deep implications for the way in which we engage in redemptive activity within cultural. Too many times, Christians recognize that Christ's redemptive work is broader than just personal salvation. This is good. Nevertheless, when it comes to societal and ecological redemption, we often look for a fulfillment that runs on the same rails as the old trajectory – through Christ (as exemplar, inspiration), yet with only a physical manifestation; there is real no heavenly dimension at all. We fail to appreciate how Christ has fundamentally changed the old trajectories. This is dangerous – it can lead to triumphalism at best, and a pure social gospel at worst.

To state the matter plainly, too often we look for social justice, or environmental renewal, or the revitalization of our cities purely in physical, earthly terms; we seek an earthly glory now, rather than the pattern of humiliation now, glory later. This makes it very easy for something like liberation theology to define its goals simply in terms of tangible, economic, “real-world” change. Such change is important. But at the end of the day when all these goals are realized, all you have done is create the very middle class which you started out critiquing. Redemption runs much deeper than simply transforming the working poor into the working middle class.

The same holds true for cities and ecology. We must never forget that Christ has already restored the land, he has created a new Zion. He has created the Kingdom of God, he has founded the one true church. These are spiritual realities, which can only be apprehended by faith. And so we as a church called to engage in real social action in the here and now, yet always pointing those we engage upward and onward to the deeper, truer, heavenly realities. The physical realities must never be seen as ends in themselves. The place where such expression happens most fully is the church (Eph 2:19-21) – this is where the work of Christ finds its climax; it is only natural that this is the place where his redemption accomplished should find its fullest expression.

In sum, then, the church has both responsibility and liberty to engage in social action. Our redemptive work in the secular sphere, however, must always be seen as secondary and derivative, and it must constantly point unbelievers back to the more ultimate realities of Christ's redemptive work in the church.

A rapid survey of the biblical and historical records yields mixed results. Certainly we are called to love our neighbor (Luke 10:27-37), to seek justice and mercy (Mt 23:23), to visit orphans and widows in their distress (James 1:27). The early church took such charges seriously – they were known for their sacrificial care of poor and prisoners, both believers and unbelievers alike. Such examples rightly put many of our modern, consumer-driven evangelical churches to shame.

At the same time, many have argued that Scripture is surprisingly silent in key areas like politics, women's rights, and slavery – Paul preached submission and service, rather than revolution (Eph 5:22-6:8; Rom 13:1); we are told to pray for our leaders, that we may live a peaceful, quiet life (1 Tim 2:2). This hardly seems to fit with the vision cast by liberation theologians and social activists.

The tension is not easily resolved – we simply cannot point to a single verse or convenient proof text that clearly defines the church's role in society. To find an answer, we need to look more deeply at the warp and woof of the Scripture. We need a biblical view of destiny and redemption. And here, the Old Testament prophets prove particularly helpful.

Modern evangelicals have often seen a sharp distinction between “spiritual life” and “the real world.” If we were to illustrate such a worldview, it might look something like this:

Many American Christians see the world of “spiritual things” as existing on something of a parallel plane to the here and now of daily living. Redemption is viewed primarily in terms of our personal destinies; the overarching concern of Scripture is seen to be equally individualized – people who are spiritually lost (usually defined as “not believing in Jesus”) somehow need to get themselves found (usually by believing the right things about Jesus, and living according to a certain moral code), thus ensuring an eternal future in heaven rather than hell.

Many American Christians see the world of “spiritual things” as existing on something of a parallel plane to the here and now of daily living. Redemption is viewed primarily in terms of our personal destinies; the overarching concern of Scripture is seen to be equally individualized – people who are spiritually lost (usually defined as “not believing in Jesus”) somehow need to get themselves found (usually by believing the right things about Jesus, and living according to a certain moral code), thus ensuring an eternal future in heaven rather than hell.In a perspective like this, the work of salvation is basically an intellectual commitment to “having Jesus as my personal Lord and Savior,” but my “real life” often continues mostly unchanged, and my “new life” doesn't really start until I “die and go to heaven.” The work of the church, then, is primarily focused on getting individuals to affirm the right facts about Jesus, that they might live happily ever after in the sweet bye-and-bye. There is very little real intersection between the two planes of existence.

The Old Testament witness, on the other hand, paints a markedly different picture of future glory. As Donald Gowan points out in Eschatology in the Old Testament, a prophetic view of the revitalized future is much more earthy, organic, and comprehensive – it envisions real life restored in the here and now, on earth (in the Promised Land, of course), rather than somewhere in the distant future. We might illustrate the prophetic vision like this:

Seen through the lens of the Old Testament prophets, “salvation” is not seen as some individual, personalized escape from this physical worldly existence to some future, other-worldly, streets-of-gold-with-harps-and-angels, spiritualized reality. No! Salvation is nothing less than a restoration of what was lost in Israel's fall.

Seen through the lens of the Old Testament prophets, “salvation” is not seen as some individual, personalized escape from this physical worldly existence to some future, other-worldly, streets-of-gold-with-harps-and-angels, spiritualized reality. No! Salvation is nothing less than a restoration of what was lost in Israel's fall.Gowan unpacks this prophetic vision of restoration in three main categories. First, the prophets do in fact envision a personal renewal. They promise that the Israelites will receive a new heart, one of flesh not stone (Ezek 11:19); it will be circumcised and holy (Deut 30:6), filled with the very Spirit of God himself (cf. Is 44:3) so they can serve God as he deserves and requires (cf. Deut 6). Second, the prophets also envision a societal renewal. They look for the gathering of Israel from the nations to which she had been scattered, her renewal as a nation, her elevation to a position of national prominence, with Zion (Jerusalem) as the city of God, and a new and glorious temple set high on his holy hill (cf. Is 2:2+, Ezek 40+). Third, the prophets also envision ecological renewal as the curses upon the land are reversed, in a virtual return to Eden as the land once more flows with milk and honey, and the river of life itself flows from the temple mount (Ezek 47).

The point here is simply this: the prophets offer us a much more comprehensive view of salvation, extending to all facets of life, rooted in the “real world.” In this view, the messiah represents the anointed one of God who will lead Israel into this new era of prosperity and blessedness.

This restoration vision becomes immensely practical when we see the connection between Christ and Messiah, between the New Testament church and Old Testament Israel, Zion (cf. Heb 12:22, 1 Pe 2:6, Gal 6:16). The redemption wrought by Christ is not merely internal, personal, spiritual (although it certainly is that) – it reaches much further.

In fulfilling all the promises of God (2 Cor 1:20), Christ's redemptive work must carry implications for all three aspects. The promised renewal of society (nation) and ecology (land) are not merely future, nor are they figurative. The church needs to be salt and light in a fallen world, living redemptively and working for its transformation, seeking to illustrate the “already” of heavenly reality in the “not yet” of our present world. This is how the gospel will go forward. And this implies that the church's work in the world is more than mere proclamation – as Harvey Conn says, we evangelize most effectively when we minister both in word and deed. The church has a responsibility to seek justice, to work for the social renewal, and we are given great liberty in terms of how we go about that task. At its best, the church should make a difference in culture and society.

Having said all this, we now need to make a vitally important clarification, one which redemptively minded Christians often overlook. Many who embrace this broader view of redemption (personal, societal, ecological) fail to consider for the surprising way that Christ fulfills the promises of old. Restoration glory only comes through weakness, suffering, and humiliation – the Messiah comes dressed in the garb of a humble servant, rather than robed in the glory of a triumphant king. That reality represents a surprising twist on the old covenant story, one which actually affects the character of the fulfillment.

In the New Testament, suffering and humiliation is a key feature of Christ's calling – this is how he is perfected, how he gains his glory. While we get glimpses of it in the Old Testament (cf. Ps 22, Is 53), this feature is not fleshed out fully until Christ himself summarizes his ministry:

“Was it not necessary that the Christ should suffer these things and enter into his glory?” And beginning with Moses and all the Prophets, he interpreted in all the Scriptures the things concerning himself. - Lk 24:26,27.Christ comes as the long awaited, glorious Messiah, and yet his glory does not come until his exultation, after his suffering.

As with the Messiah, so too the people who are formed in his image. We are saved through faith, yet we are not immediately translated to a state of glory. Instead, we too are called to a ministry that is characterized by weakness, foolishness, and suffering (cf. 1 Cor 1:18-25, 2 Cor 4:7-18, Phil 1:29). Our sanctification is progressive. We experience the fulfillment of the promises, but with a surprising already-not-yet texture to them. In personal redemption, I really do have a new heart that is changing me now. But I will not receive the fullness of that new heart, in all its overplussed glory, until Christ returns.

The promises are indeed really fulfilled. But they are not yet fully fulfilled. The heavenly reality of ultimate redemption is breaking into the here and now – the now-redeemed me is actually a the pointer to the then-to-be-redeemed me which is yet to come. So Christ, in fulfilling the promises of old, actually alters the trajectory of those promises, and fulfills them not in a single moment, but over the course of our lives, finding its full expression only at our glorification. If this is how Christ fulfills the promise of personal redemption, may we not also expect a similar fulfillment in the societal and land dimensions as well?

Once again, a diagram may help illustrate:

What we see here is the image of Christ as cornerstone (1 Pe 2:6-8). Not only is he the foundation of redemption, but he actually changes the trajectories of redemption as well – he “turns the corner” if you will, fulfilling the promises in a surprising manner. He creates a new people, a new temple, a new kingdom. None of these are altogether different trajectories – there is a definite continuity with the old – but neither are they merely the same trajectories. There is a reason why we speak of Christ's work as a “new covenant.”

What we see here is the image of Christ as cornerstone (1 Pe 2:6-8). Not only is he the foundation of redemption, but he actually changes the trajectories of redemption as well – he “turns the corner” if you will, fulfilling the promises in a surprising manner. He creates a new people, a new temple, a new kingdom. None of these are altogether different trajectories – there is a definite continuity with the old – but neither are they merely the same trajectories. There is a reason why we speak of Christ's work as a “new covenant.”Not only does Christ alter the trajectory of God's redemptive promises – as the cornerstone, he also acts like a prism which splits each line of redemptive activity and refracts them, giving them the already-not-yet character which we have described above for our personal salvation. As with personal, so too the societal and ecological. Each line of promise experiences the same already-not-yet character of fulfillment: humiliation now, glory later.

This has deep implications for the way in which we engage in redemptive activity within cultural. Too many times, Christians recognize that Christ's redemptive work is broader than just personal salvation. This is good. Nevertheless, when it comes to societal and ecological redemption, we often look for a fulfillment that runs on the same rails as the old trajectory – through Christ (as exemplar, inspiration), yet with only a physical manifestation; there is real no heavenly dimension at all. We fail to appreciate how Christ has fundamentally changed the old trajectories. This is dangerous – it can lead to triumphalism at best, and a pure social gospel at worst.

To state the matter plainly, too often we look for social justice, or environmental renewal, or the revitalization of our cities purely in physical, earthly terms; we seek an earthly glory now, rather than the pattern of humiliation now, glory later. This makes it very easy for something like liberation theology to define its goals simply in terms of tangible, economic, “real-world” change. Such change is important. But at the end of the day when all these goals are realized, all you have done is create the very middle class which you started out critiquing. Redemption runs much deeper than simply transforming the working poor into the working middle class.

The same holds true for cities and ecology. We must never forget that Christ has already restored the land, he has created a new Zion. He has created the Kingdom of God, he has founded the one true church. These are spiritual realities, which can only be apprehended by faith. And so we as a church called to engage in real social action in the here and now, yet always pointing those we engage upward and onward to the deeper, truer, heavenly realities. The physical realities must never be seen as ends in themselves. The place where such expression happens most fully is the church (Eph 2:19-21) – this is where the work of Christ finds its climax; it is only natural that this is the place where his redemption accomplished should find its fullest expression.

In sum, then, the church has both responsibility and liberty to engage in social action. Our redemptive work in the secular sphere, however, must always be seen as secondary and derivative, and it must constantly point unbelievers back to the more ultimate realities of Christ's redemptive work in the church.

7 Comments:

One brief comment, simply for the sake of full disclosure - I am using Gowan for my own purposes here, as a starting point. I suspect he would agree with my summarization of OT eschatology (see diagram 2), although he himself doesn't draw it out like this. I am almost certain that he WOULDN'T agree with where I take things (diagram 3). So just to be clear here, if there are weaknesses or flaws in this paper, they are mine rather than Gowan's.

Christian,

you have some great thoughts here, thanks for sharing. Let me add some comments to it. The first is a preamble- I'm a pretty avid environmentalist and try to be an amateur green theologian- so most of my comments are on this point.

I like very much the recognition of justice not just in society in the land. However, near the end of your post you have a conclusion that to me did not seem to flow from the body of the work. You say "The same holds true for cities and ecology. We must never forget that Christ has already restored the land, he has created a new Zion......[and] Our redemptive work in the secular sphere."

To me this doesn't jive with the idea of the already/not yet movement of redemption- which I think extends to the physical world. Rom. 8:19-23 "For the creation waits with eager longing for the revealing of the children of God; for the creation was subjected to futility, not of its own will but by the will of the one who subjected it, in hope that the creation itself will be set free from its bondage to decay and will obtain the freedom of the glory of the children of God. We know that the whole creation has been groaning in labor pains until now; and not only the creation, but we ourselves, who have the first fruits of the Spirit, groan inwardly while we wait for adoption, the redemption of our bodies."

The land awaited the incarnation and awaits its complete redemption. I get worried that the notion of 'God already having restored the land' couples too easily with the Christian anti-ethic of "its all going to burn up anyway". The churches creation-care ethic is downright shameful, but it is born from our theology and (I think) false dichotomies.

Also the last line I quoted, "Our redemptive work in the secular sphere" seems to reinforce the dichotomy that you were, at least partially, trying to break down int he beginning of your post. If the earth is the Lord's and everything in it, if Jesus is Lord of all, if the temple curtain was torn that God's Spirit may exit, then there is no secular sphere. I think this dichotomy is the product of the enlightenment.

Thanks for posting this, its good stuff. I especially like the additions you have made (the stuff that isn't Gowan's :) Jesus as the cornerstone refractory is a very helpful way of understanding the Kingdom of God and the gospel.

Danny

I'm not sure I could stand anymore right in line with your discussion here. Bravo! Great post!

Montana holds a very special place in my heart, and one fact that bothers me the most is the lack of solid Reformed churches in such a large state. Knowing that you and Ryan intend to plant a church in Missoula is something I get more excited about everytime I think of it.

I want to add two small comments. First, just to add to the beginning argument in the post, my growth group has been studying through the Pastoral Epistles and we will be finishing up Titus shortly. All of these letters seem to support what you have discussed here, but the second chapter of Titus especially does I think.

Paul seems to give Titus a set of Christian ethics for the churches of Crete to live out, and these ethics are lived out in their society and culture. In contrast to other religions of that day, Christianity calls men and woman to be submissive, repectable, and self-sacrificing towards the government authorities and to all men in such a way that the Gospel ultimately will begin to have a stabalizing effect on society and culture rather than a revolutionary effect.

Maybe it seems too simple, but how we live everyday in the world is intimately linked to the Gospel being carried throughout the world, impacting lives, societies, cultures, and the earth itself. Christianity call us to subversive warefare against the way of this world, and our most deadly weapon is love. The finishing blow to Satan was the willingness of Christ to give up is own life for us.

Second comment: As we now "rise" in a redemptive way this side of the Cornerstone as you mentioned what type of "Edenic" state are we headed for? I might have missed this while I was reading, but I wonder if that is the best way to put it. For instance, we all know that we, ourselves, are headed towards a fully redeemed existence in heaven but I hope we understand that this existence will be much greater even than Adam's initial existence. I also then would assume that this is true for everything you have included in this post as being redeemed.

To put it another way, Adam began life in the Garden which is only the beginning of the story, and by the end God's people are destined for the New Jerusalem, a civilization as opposed to a garden.

Let me attempt to get to my point. In the OT picture of God leading the people out of Egypt in ultimately into the promised land, they arrive with work to do. They must first drive out or kill the pagans in the land. Then they must rebuild or establish their own fortified cities. Before everything is done, a Temple, a house for God must be built so that God may dwell amoung them, etc. Esentially, a civilization must be established.

I think this story backs up further what you have discussed here. In the Church recently, it seems we have been content to move into the promised land, pitch tents, and wait out this gnostic view of heaven we have in our minds instead of realizing that we are "already" in the promised land, and are called to help out in the work of redemption in ushering in the New Jerusalem, which is happening now, but will be fully complete in our Bridegrooms second Glorious Appearing (not yet).

Ok, guys, great comments one and all - you've inspired at least a dozen different lines of thought (so you are definitely adding to the discussion here).

Let's see, where to start.

There are a couple of things I'm really affirming in the post:

1. I really want to affirm a strong redemptive connection between the work of the church and the broader society and environment. I think the OT view of redemption is very comprehensive and organic.

2. I also want to affirm that Jesus fulfills ALL of the OT promises - but in a way that alters (overplusses) the original trajectories (this is what I'm talking about w/ that 3rd diagram. The people of God are transformed, from Israelites (Jews) to Christians (true-Jews). The promised land becomes the kingdom of God. The city of God (and even the temple of God) morph into the church as spiritual house of God and community of faith, both of which are founded on Christ as chief cornerstone. The promise to the faithful shifts from 'the good life' to 'eternal life'. There is both continuity and discontinuity in the fulfillment of all of these.

3. The fact that the original trajectories are altered in the fulfillment means that as we think redemptively about society and ecology, we need to be careful not to think about these things simply in old covenant, earthly, physical categories. There will still be a physical component, but I expect it to look different.

For example, I'm not holding my breath waiting for a physical temple to be rebuilt in Jerusalem. Spiritually speaking, I see Christ as the new temple, with Christians being built as living stones upon him (cf. 1 Pe 2:5). This is a spiritual house, and yet there remains a physical representation in the visible church. The former is pure and heavenly; the latter is weak and earthly. But both are real.

We could say the same thing about me personally - there is the new creation me, already seated in the heavenlies w/ Christ (Eph 1-2); there is the old me, wrestling with indwelling sin and external suffering, struck down but not destroyed. But both are real. I am already experiencing eternal life.

If these things have changed this way (to include both spiritual and earthly realities coexisting in an already-not-yet tandem), then I expect redemptive promises for society and ecology to be transformed as well.

4. I'm not entirely sure what this looks like yet (that's where I need your help still!).

-I DO think we need to be careful not to simply define 'redemption' the way secularists do - as an ultimate end in and of itself

-I DON'T think we want to see 'redemption' as detached from society, ecology - evangelicals have done that far too often, IMO.

-I DO think there must be some connection between the church's 'redemptive work' in the physical/secular sphere and spiritual/churchly spehere. The former is derivative and secondary (but in no way optional or unimportant!), pointing to the greater reality, which is primary.

5. I am pretty certain that the character of redemptive activity in all areas will mirror that observed in Christ first, and in our personal transformation second - a pattern of humiliation, weakness, and suffering servanthood now, followed by glory and exultation later.

And I note that we are not used to thinking this way. Consider how much 'redemptive' work (social justice, environmental protection, etc) is pursued through legislation rather than heart change. I'm not saying legislation is bad - but I'm saying that in many cases we Christians who actually want to live redemptively in society are simply buying into society's definitions - both in terms of ends and means.

So my theology here drives me in the direction of a deep seated conviction that our goals and means should be fundamentally Christian, personal, aimed at heart change, embracing weakness instead of grasping after power, serving others rather than serving ourselves, etc. And it should look like foolishness rather than wisdom to an unbelieving world.

All that just in response to what Danny said (and I'm not even sure if I answered your concerns).

Now that I read Chris' comments, I think (hope) this may address some of those as well? Yes? No?

Feel free to keep the comments coming here guys - as you can see this is very much a work in process. At this point, I feel like I see the theological rationale fairly clearly, but I am still attempting to think through the implications for the church.

(and this whole thought process is itself an instance of redemptive activity in the church!)

Hi Denny,

Thanks for the reminder on the importance of keeping it simple. That's actually something I have tried to do in this post, but obviously mileage is going to vary depending on both reader and writer. But I agree that we want to avoid making things more complex than they are.

At the same time, I think we also need to remember that God's salvation is 'a mystery', something that is far bigger than all of us. As such, it shouldn't surprise us when it stretches our brains (as well as our hearts). If it's NOT doing that, if it is something which I think I've mastered, chances are I'm not seeing it as clearly as I ought to. The real test is not 'is it simple' but rather 'is it biblical'.

In regards to your specific points, I have a feeling each of us has very different ways of looking at Scripture - we probably disconnect shortly after that first diagram. In cases like this, its often very helpful to try and understand how the other person is thinking, to arrive at the conclusions they do. I _think_ I know where you're coming from (because I'm pretty sure I used to be there myself). To understand where I'm coming from, you'll probably want to try and appreciate how I see a deep continuity between old and new testaments, between Israel and the Church, between what the prophets were pointing to and what the church is to be about in the here and now.

That may all sound completely foreign to you, but hopefully you'll think "Hmmm... how can a Christian like Christian think this? Where's he getting it from in Scripture? What assumptions is he making? etc"

If my comments serve to stimulate your thinking in that regard, I'll be happy (even if we don't agree on particulars).

Blessings,

Christian

I've agreed with everything you have said Christian, except one that I wonder about. In that Jesus has fulfilled the OT promises- is the promised land now the Kingdom of God, or is the promised land now the whole world (which is why a new earth comes in Revelation)? I think maybe this is what I am shaky on- the 'Kingdom' becomes a very ethereal reality, whereas the promised land was real, earthy, something you can touch and feel. Now I think I am simplifying what the Kingdom is, but as I said, I think the promised land is now the whole world.

what do you think?

time to add another question to a very lenghty and edifying discussion...

How does Scriptural imagery play into this discussion? What I mean is that we tend to read Revelation 19-22 as a physical city that will have all of the components that are described in those chapters. We tend to think of the church as a literal building where Christ is a literal cornerstone and we are bricks.

Now obviously there is some literal-ness to this imagery. But on the other hand there isn't. These are earthly metaphors meant to represent spiritual, heavenly realities. Likewise, the New Jerusalem is an earthly metaphor and the purpose is to blow the readers' minds about any city they have ever imagined. The best of OT imagery culminates in the New Jerusalem.

How do we think about all of this in practical, concrete ways while at the same time keeping in mind the imagery that is being used in Scripture to describe these realities. My brain is getting fuzzy just thinking about it.

Part of our problem, I think, is that we are equating earthly realities (of the already) with spiritual realities (of the not yet).

Does that question make sense? It's 1:45 am and I'm not sure I can even make a coherent statement at this point, so let me know if I need to flesh this out some more.

Post a Comment

<< Home